This post probably has more acronyms than any other post I’ve ever written. But don’t blame me—blame organized racing for being, well, not that organized.

This past weekend, I was fortunate enough to visit the Long Beach Grand Prix for a second time (my first was in 2013). Like last time, I was treated to the event by my friend, Dr. Christopher Martin, who also happens to be my former teacher. But unlike last time, this time, Allison came with me. It was fun to bring her to see all the loud cars. (That’s two car events in one month!)

I thought I would share the most exciting part of the day. But that comes later. Before I share that, some background is necessary.

Organized Racing ¶

In modern organized racing, the Triple Crown of Motorsport is a comprised of three titular events:

- Indianapolis 500 (IndyCar)

- 24 Hours of Le Mans (Non-open-wheel)

- Monaco Grand Prix (Formula One (F1))

For the purposes of this post, let us focus on the second cog in the Triple Crown: the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Held at the Circuit de la Sarthe in France, the 24 Hours of Le Mans is a grueling race aimed at testing team resolve and endurance, rather than outright speed (this contrasts with “Grand Prix” racing, such as IndyCar and F1). The race has always featured multiple classes of vehicles—all competing on the track at the same time.[1]

In 2012, the 24 Hours of Le Mans came under the umbrella of the FIA World Endurance Championship (FIA WEC), a series currently comprised of 9 endurance races all across the globe.

Today, there are four classes in FIA WEC:

- Le Mans Prototypes (LMP)

- LMP1: More power than LMP2; faster in a straight line

- LMP2: Less power than LMP1; slower in a straight line

- Le Mans GT Endurance (GTE)

- Pro: Cars based on current model-year [homologated] street cars (piloted by professional race car drivers only)

- Am: Cars based on previous model-year [homologated] street cars (can be piloted by race car drivers, but typically contain an amateur or two per team)

American Le Mans Series → IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship ¶

Since its inception, the 24 Hours of Le Mans has inspired many similar such events, some with and some without the endurance component.

The American Le Mans Series (ALMS) was, as expected, inspired by the 24 Hours of Le Mans, but instead of focusing on just one race, ALMS consisted of a series of races, in which several teams competed for class and overall victories.

In 2014, the American Le Mans Series merged with another Le Mans Series-inspired competition, Rolex Sports Car Series, forming the United Tudor WeatherTech SportsCar Championship, sanctioned by the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA),

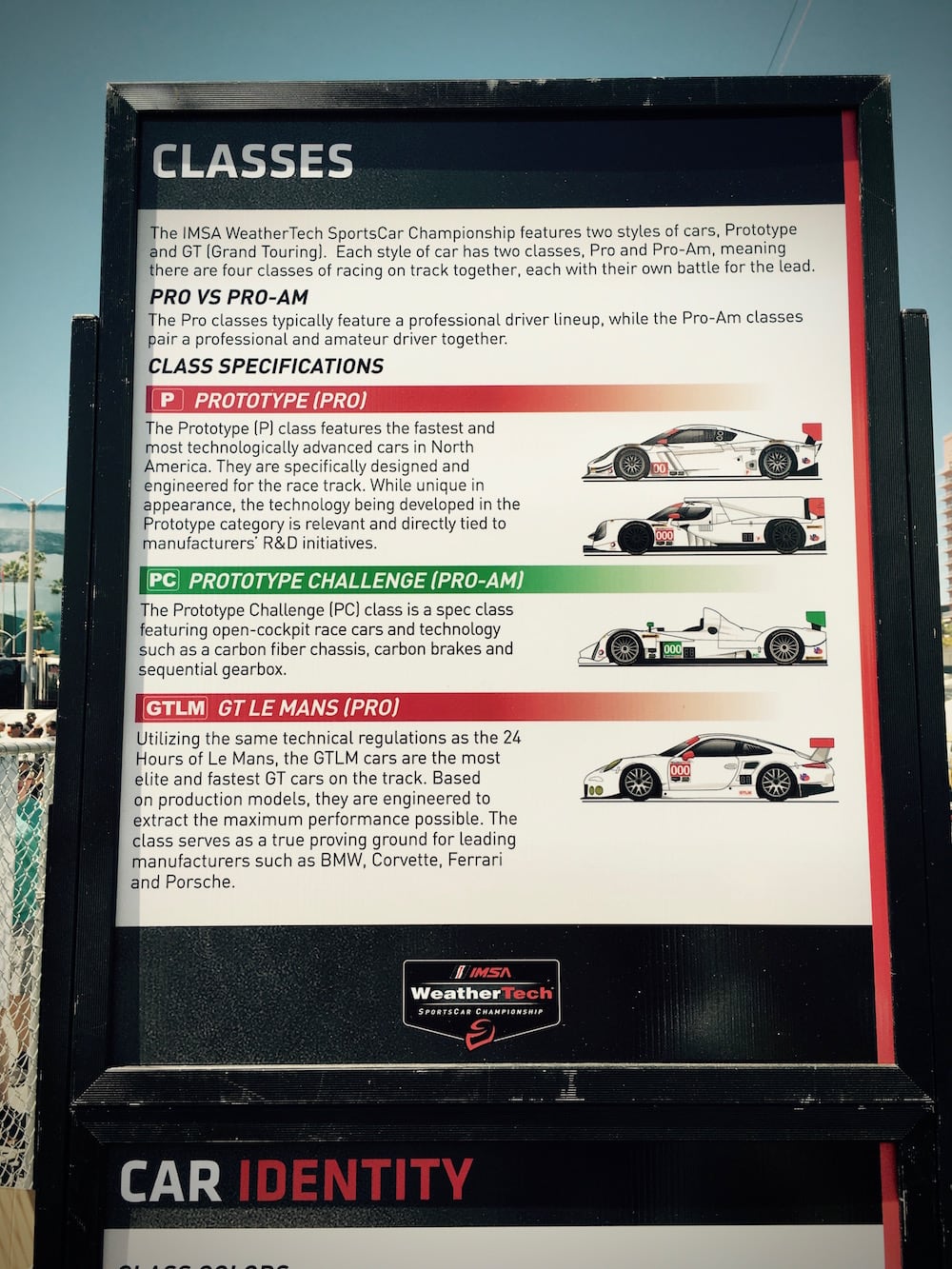

In the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship (IWSC), there are four classes of cars, loosely based on the classes used by the FIA WEC:

- Prototype (P): Similar to the LMP1/2 classes

- Prototype Challenge (PC): Carried over from ALMS, these cars are made by Oreca using Chevrolet motors

- GT Le Mans (GTLM): Similar to the GTE-Pro/AM classes

- GT Daytona (GTD): Similar to the ALMS GTC class (using GT3 Cup cars)

For Me, It’s All About the GT Cars ¶

In case it’s not immediately obvious, the overall winners for most races are the Prototype or Prototype Challenge cars (remember, these are the most `race car` of all the competing race cars in Le Man style racing).

But it’s not just about the overall winners. It’s just as much about the class winners.

The grand touring (GT)-class cars have always been my favorite, because they’ve always been based on popular street cars such as the Corvette Z06, Porsche 911 and Audi R8, to name a few.

Here’s why the GT class is so cool:

Most of the current Porsche GT class cars are based on the [current generation] GT3, a street car that is incredibly performant as it is. For most GT class entries, the race car version features increased displacement, lots of weight reduction, and other performance-increasing modifications.

But, to the average racegoer, a 991 RSR or GT3 R is still recognizable as a GT3—at least as far as general proportions goes.

Similarly, the C7.R looks a whole lot like the C7 Corvette.

And the Mopar race cars look like street Vipers, etc.

That’s awesome! That’s what makes Le Mans-style competitions so neat: they feature race cars that have street counterparts that anyone could have (well, anyone with enough money).

IWSC at Long Beach 2016 ¶

The street track at Long Beach, CA is the third of 12 stops for the aforementioned IWSC.

I only attended on Saturday. Friday is practice/qualifying for the IWSC and other races throughout the weekend. Saturday is practice/qualifying for IndyCar, and the actual race for the IWSC. Sunday is the IndyCar race.

For the IWSC race on Saturday, Corvette Racing had two Daytona Prototypes starting in position one (P1) and position two (P2). And Corvette racing also had the P1 and P2 spots for the GTLM class as well (C7.R’s).[2]

Porsche Works had two GTLM entires, the #911 and #912 cars (both 991 RSR’s), piloted by Nick Tandy/Patrick Pilet and Frédéric Makowiecki/Earl Bamber, respectively.The race is 100 minutes, which I love, because it means that even during yellow flags, the time keeps on ticking at the same pace.[3]

Those Naughty Germans ¶

For the first half of race, the RSR’s generally held P1 and P2. Around halfway through, they suffered a penalty for speeding in the pits. Afterward, they loosely held P3 and P4 for the remainder of the race. A few minutes before the end, things changed for the Porsches: the P2 C7.R crashed into the wall, putting Tandy and Makowiecki in P2/P3, right behind Tommy Milner in the P1 C7.R. At turn 11 (the hairpin—that’s where we were sitting), Makowiecki rear-ended the P1 C7.R, allowing Tandy in his #911 to take the lead. A couple minutes later, that car won the GTLM class.

Admittedly, I was full of glee when Tandy squeaked by the inside of the turn to take the lead.

“Yay Porsche!” I almost certainly exclaimed. That was my initial feeling, at least.

Then something got my attention. I heard the C7.R throttle up as it engaged reverse gear and backed up. And then it sat there for a split second, as if to say, “Hey jerk RSR driver, are you going to go, or can I finish the race now?”

That scene stuck with me, because like all well-cam’d V8’s, the C7.R’s throttle-up was exhilaratingly loud.[4] And that split second seemed to last for ages. And somewhere in the midst of all this, the thought occurred to me: “That Porsche intentionally bumped the Corvette.”

In fact, there should be no doubt in anyone’s mind: the bump had to be intentional.

As Stef Schrader of Jalopnik notes, That’s not how racing works. That’s not a line that would have made it around that tight bend at that speed with a Corvette also trying to make it around the corner.

Indeed, Makowiecki and Tandy are just too good at their jobs for me to believe that Makowiecki bumping Milner was an accident.

This kind of thing isn’t supposed to happen in Le Mans style racing. (Or in IndyCar or F1, for that matter.)

It’s not NASCAR, after all.

And so, even though I was incredibly happy that Porsche Works won the day, it felt like an empty victory. Yeah, they won, but they won it being less than honorable. The Corvette lost for no fault of its own—it lost because the competition was kind of dirty.

So, I’m conflicted. I’m happy that Porsche Works won the GTLM class. But I’m sad in how they won. Still, the next race is another opportunity for Porsche Works to win …the right way. Let’s hope so.

See you next year, LBGP.

This stands in contrast to other racing events, such as NASCAR, in which all of the cars are basically the same. Such events derive competition in driver skill, rather than team engineering (since all the cars are the same). ↩

Corvette Racing is an absolute beast of a racing team, and has been for many years. ↩

This is in contrast to a lap-based race, in which time seems to drag on much slower during yellow flags.

Besides this track, I’ve only been to one other racing event, and that’s the last few years’ Auto Club 400 (NASCAR). That race is based on the number of laps completed—not time elapsed. Lots of yellow flags at Auto Club sure seem to make the race last forever. ↩

I love the sights and sounds of Le Mans style races. The cars are all so different, and each one sounds strikingly different.

The howl of the RSR’s upshift on the straight away sounds less throaty and meaty compared to the C7.R’s absolute thunder of a motor. And the Ford GT’s throttle-blip before a downshift is absolutely guttural. Great stuff. ↩