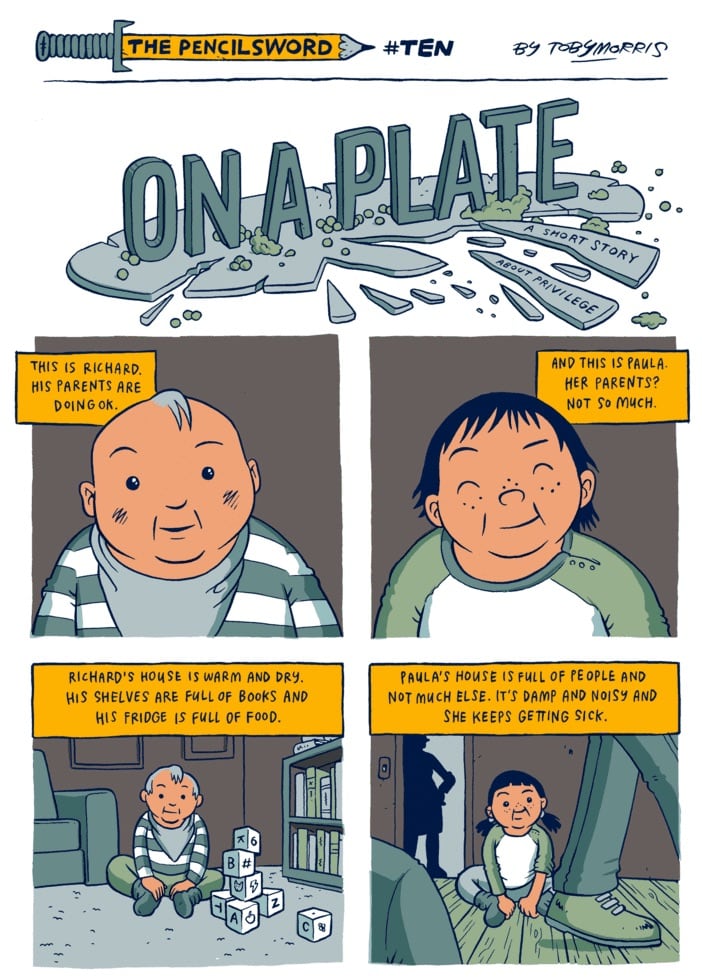

I recently saw a rather clickbait-y headline, “A short comic gives the simplest, most perfect explanation of privilege I’ve ever seen.” That headline landed me to a piece on The Wireless, with an illustration by Toby Morris entitled The Pencilsword: On a plate.

Over the past few years, I’ve become increasingly aware that my life as it is was not achieved soley by my own works, but also (if not more-so), because I am privileged.

Educational Privilege ¶

I am the epitome of Seventh-day Adventist Education™.

I wasn’t born into Adventism like many of my friends; my parents converted when I was in 2nd grade. In fact, the only reason they become Adventists is because of my experiences at the “local Christian school,” Modesto Adventist Academy. My parents probably enrolled me for the same reasons most parents enroll their children in private Christian education: it’s supposed to be better.

Years later, no amount of my cynicism could deny this: I believe private [Christian] (?) education is better.

Stripping away all the tenants of said education, such as student-teacher ratio, SAT/ACT scores, college acceptance, I think it all boils down to this: private school is a shield. It’s a shield of privilege.

The teachers were paid less, but cared for their students. I was always encouraged to learn more, do more, be more.

High school prepared me for college, and I went. College prepared me for dental school, and I went.

All of my education has been in the Adventist school system, and all of my education has been privileged to me because I am Adventist.

Familial Privilege ¶

After finishing school, I worked for a few years as an associate dentist in Southern California. The pay was pitiful, and the experience was okay, more or less. Some might agree that “I did my time” (I’m not so sure).

But when Allison finished school, we moved back to Northern California, where I started a new job working with my father-in-law. There was no long application process, no working interview—I just started working. I go in to work, do dental things, go home (and get paid).

If I wasn’t working for my father-in-law, I’d no doubt have to find a job working for some other dentist. Or, I’d have to go back to working as part of a larger dental service organization, which is worse than “paying my dues.”

My job is a privilege of being a part of this family.

Pastime Privilege ¶

And while I don’t currently enjoy the aforelinkedto pastimes to their fullest extent,[1] someday I will. It may not happen all at once, but eventually, it will happen.

That I can meticulously research my future pastimes on Retina screens whilst lounging on a comfortable couch in an air-conditioned room with lots of windows and views of birds and the sky—that speaks volumes to my obvious state of privilege.

The Guilt of Privilege ¶

Through Toby Morris’s comic strip, I realize this: for all the privileges bestowed upon me, I feel guilt.

I feel guilt because there are people who grow up without a home that is nurturing. There are folks who don’t have teachers who care. There are people whose career isn’t just handed to them like me.[2] People without supportive spouses, loving children—there are so many such people out there.

I feel guilt because I have so much to be thankful for, while many others don’t even have the ability (no screen) nor time (working two jobs) to read this rather existential blog post.

What’s Next?© ¶

I’ve been following The West Wing Weekly since its inception. I’d already heard of Hrishikesh Hirway, because I subscribe to his other popular podcast, Song Exploder. I didn’t know who Joshua Malina was, both because I’m uncultured, and also because I haven’t seen past Season 3 of The West Wing.

Each episode of the podcast is almost as fun as seeing a West Wing episode for the first time.

I hadn’t recognized this bit before Hirway and Malina mentioned it, but one of President Bartlet’s frequent refrains is the question “What’s next?”

I can’t remember every episode for which the phrase is uttered, but I do know this: it colloquially refers the constant push for progress. On a literal level, “progress” is the progression the Bartlet administration’s agenda. On a meta level, “progress” is the progression toward the betterment of the world.

It seems appropriate to use that same colloquialism to describe my recent state of guilt, and more importantly, what to do about it.

Can I give back all the privilege that’s been given to me? Should I extrapolate all the financial gain I might achieve in my life, so that by the time I die, I will have made an equal penance? Do I need to take a Walk of Shame?

No, none of those options are possible or even practical.

Instead, the best payment for my privilege seems to be this: awareness.

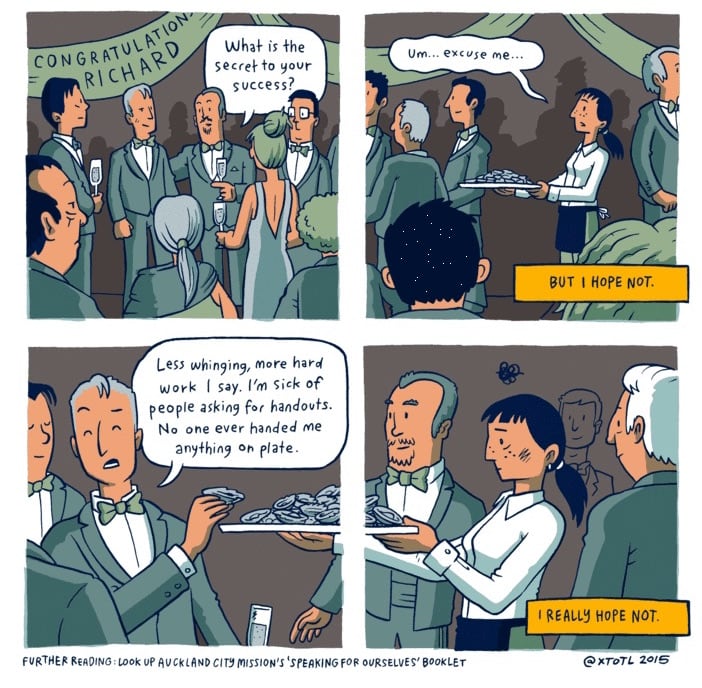

Let’s revisit Morris’s comic one last time. Specifically, look toward the ending, when the “privileged” person is asked how he made it so far.

In the comic, his answer, “No one ever handed me anything on the plate” stands in stark contrast to the “unprivileged” girl, depicted as a server at the same gathering. Set aside the wonderful juxtaposition of the two lifes, and focus more on the Privileged’s attitude.

It’s an attitude frequently (yet unofficially) espoused by the elites, and one I even occasionally find within myself. It’s pervasive because it speaks to our innate selfishness. We all like accolades, and we are all quite dismissive when it is suggested that contrary to our own endeavors, we didn’t do it on our own. Indeed: it takes a village to raise a child. No one got where they are without the help of someone else. If one is successful, they are likely privileged.

Past the guilt and through this awareness lies an acknowledgement: we the privileged must not be so quick to judge, but instead, quick to accept.

Right now, my enjoyment of Porsches and mechanical watches is limited to endless hours of research, planning, and pining over them. But I’ll go ahead and equate potential/future pastimes with said realities for the sake of argument. ↩

I don’t want to be too self-deprecating: I was in school forever, and towards the end, it was laborious and tedious. I suppose it is okay to relish in some level of accomplishment for this feat. ↩